Mike Tyson is well-known for his quote, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” As a strength and conditioning coach, do you have a plan when you or your athletes get “punched in the mouth?”

I know I didn’t. I have been obsessed with discovering and utilizing the most optimal methods for increasing strength, power, speed, and endurance just like many other strength and conditioning coaches. However, this quest is usually focused on the healthy or non-injured athlete. That was also my focus. Then, one day, I was thrown into rethinking the way I’ve always done things.

During my time as a coach for women’s soccer and women’s basketball, the inevitable had occurred: an athlete experienced a season-ending injury by tearing their ACL. This was our equivalent to getting punched in the face, and it propelled me to dive deeper into the return-to-play process in search of a more effective rehabilitation protocol.

We can all agree that we are doing our best to reduce the likelihood of injuries from occurring, but how are we measuring and monitoring to ensure the likelihood that these injuries won’t happen again? I wrote this article to share our processes at DePaul University of having checkpoints during the return-to-play process (RTP) and how they impact progressions. The information found in this article is based on an athlete returning from an ACL injury in women’s soccer and the checkpoints created by myself, our physical therapist Ted Kurlinkus, and our Director of Sports Medicine Sue Walsh. This protocol was inspired by current research available and other practitioners who are doing remarkable work with this subject. The information should not be taken as gospel since it fits our unique situation and the equipment we have available. Rather, I hope this article inspires other coaches to adapt a similar framework that best fits their situation.

With creating checkpoints for RTP, it is important to consider that the process ultimately needs to be adaptation-led. While I provide timelines that have worked well for us, each RTP depends on the individual, what that athlete needs to look like at the end of RTP, and the physical qualities needed to perfect that form. Certain athletes may have a larger requirement for absolute strength and power, whereas other athletes may require more relative strength work and work capacity. Once you identify the qualities that underpin the sport form, you can create a logical sequence to structure these qualities in order to potentiate them. This will drive the sport form to the maximum point at the end of this process. This is typical as any strength and conditioning coach usually works from general to specific throughout a periodization layout.

Weeks 1-2 : Recovery

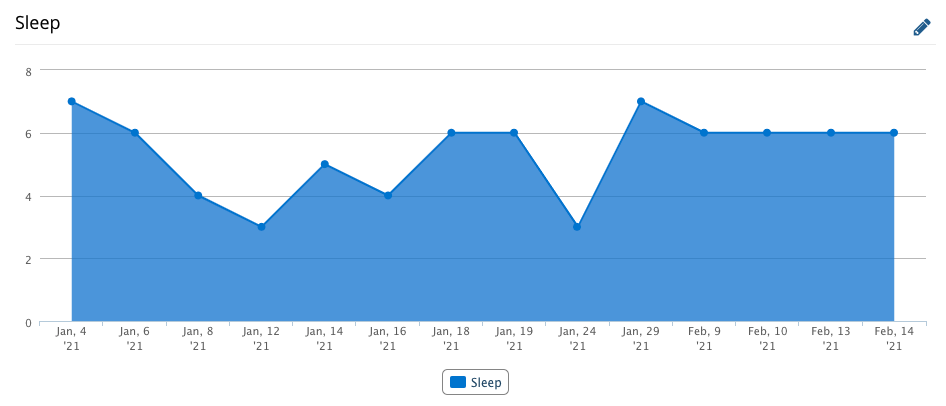

The athlete should dedicate the first two weeks post-surgery to recovery. Consistent and sufficient sleep should be particularly emphasized as a priority in this time period given how ACL reconstruction surgery is traumatic to the knee. “Sleep has been shown to have a restorative effect on the immune system, the endocrine system, facilitate the recovery of the nervous system and metabolic cost of the waking state and has an integral role in learning, memory and synaptic plasticity, all of which can impact both athletic recovery and performance. ” (Doherty et al., 2019)

Moreover, most of the body’s essential processes such as body temperature, hormone release, and eating habits operate on a 24-hour internal clock known as circadian rhythm (Guo et al., 2014). Any disruption to the athlete’s circadian cycle also disrupts many processes in their body, including recovery. It is worthwhile to educate athletes about the importance of maintaining a proper circadian schedule in order to optimize their recovery. This means being diligent about keeping a consistent sleep schedule that is aligned with the circadian biology.

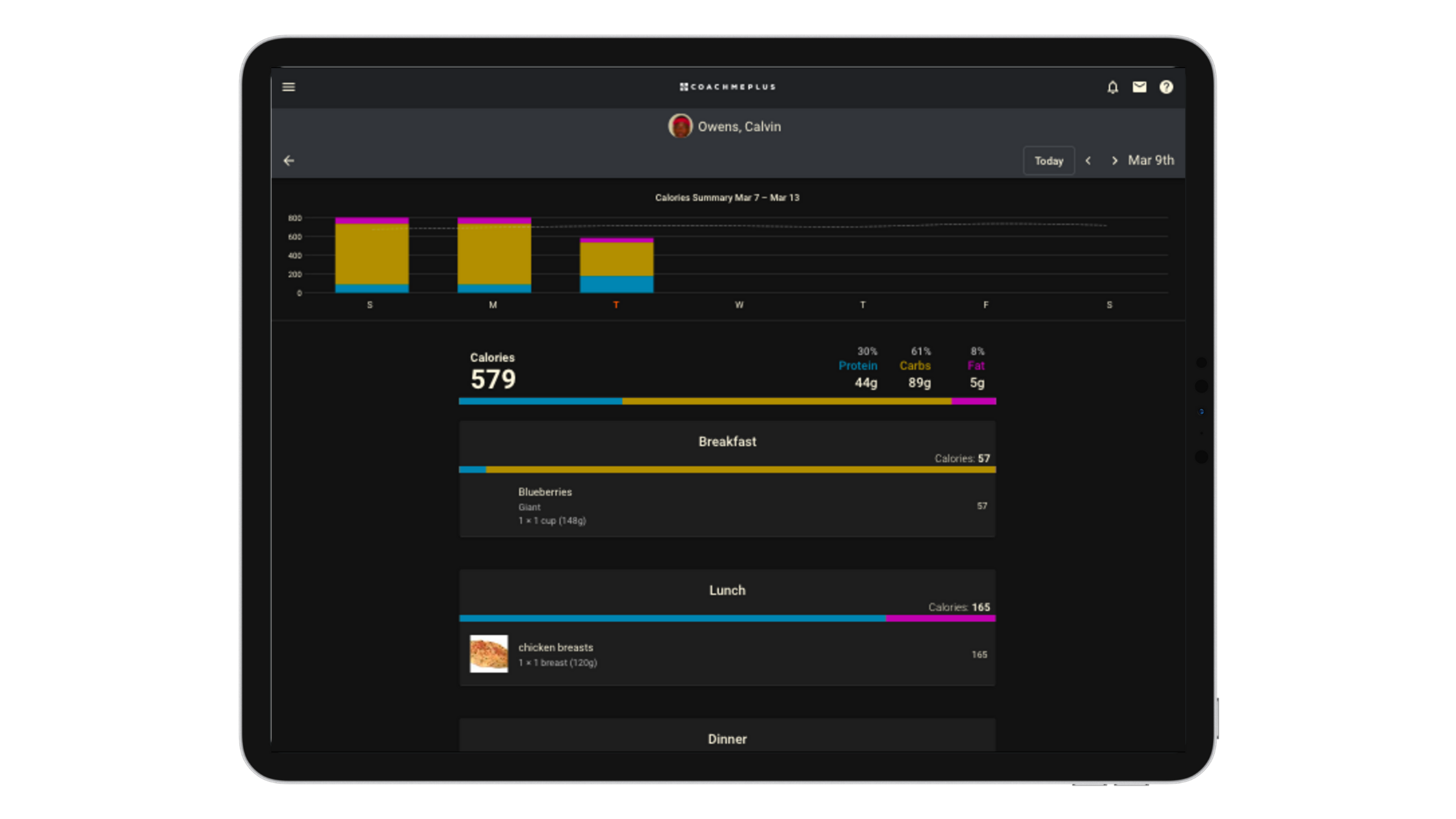

Proper nutrition should also be a priority. Assess the unique needs of your athlete to consider any supplementation that is required in addition to a proper diet. Cumulative macronutrient deficits have important clinical outcomes in surgical intensive care patients; thus it is recommended to eat at least at maintenance calories following surgery (Yeh et al., 2016). For most athletes, this is generally about 15-20 calories per pound of bodyweight. In addition to adequate amounts of protein, carbohydrates, and fats, one may need to consider additional supplementation for the following: calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C.

Weeks 3-8: Return to Fitness

Our training in the weight room begins after the 2 weeks of recovery. During the initial 2–4 weeks, the athlete will see the physical therapist and perform the basic range of motion exercises in order to get full extension in the knee and get the quadriceps firing. Much of the training during this first phase occurs with the physical therapist, but I begin to train the opposite limb which will encourage cross-education. Cross-education describes the strength gain in the opposite, untrained limb following unilateral resistance training (Hendy and Lamon, 2017). Communication with the physical therapist is important during this phase to ensure the acutely post-operative athlete is not being overloaded to allow for appropriate healing. The main goal of this cycle for me is to develop strength in the non-surgical limb. The checkpoints for this timeline include:

- Passive knee extension of zero degrees

- Passive knee flexion of 125 degrees plus

- Single leg squat test

- 1RM test performed on a 45-degree leg press, occurring on the non-surgical side

- 1RM max test on a prone hamstring curl machine, occurring on the non-surgical side

During this phase, the PT is making the call when it is time to advance to our second phase of training. This occurs when the athlete demonstrates good technique and alignment during the single leg squat and regains full range for passive knee flexion and extension. I am concerned with strengthening the non-injured limb and may retest once every 3-4 weeks.

Once the PT gives approval, I can begin to train the surgical limb in the following phase. Conditioning may include steady state bike workouts if ROM allows and/or non-impact circuits and is typically performed the day after the strength session.

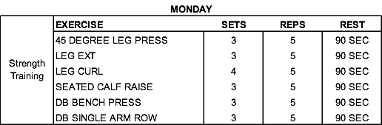

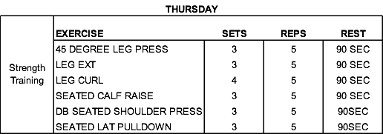

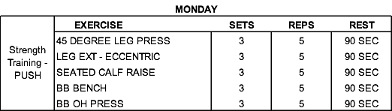

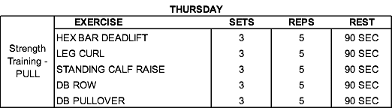

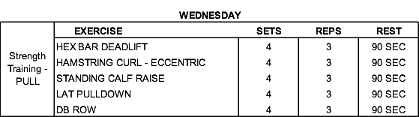

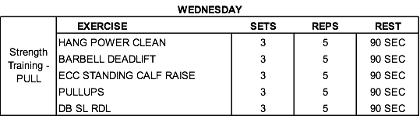

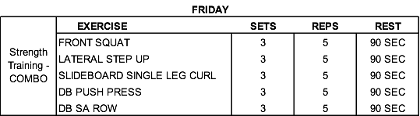

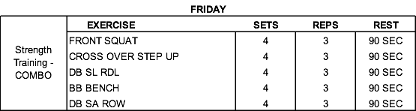

Sample weight training block from phase 1:

The volume of sets and reps is kept the same throughout the phases, but progressive overload is occurring on a weekly basis.

Weeks 9-12: Basic Strength

In this phase, many of the checkpoints are led by the PT. Since strength in both limbs is a goal, I may add more checkpoints to monitor this quality and assess the strength in the injured limb versus the non-injured limb. It is assumed that both limbs are still considered weak at this point, so the overall emphasis is to make the athlete stronger while considering the asymmetries between each limb. Once the athlete achieves the goals outlined below, they progress into the next phase. The testing during this phase will most likely occur every 3 to 4 weeks, or as needed. The checkpoints for this timeline include:

- Passive knee extension equal to the other side

- Passive knee flexion of 125 degrees plus

- Single leg bridge test > 85% compared with the other side and >20 reps

- Single leg calf raise test >85% compared with the other side and >20 reps

- Side plank endurance >85% compared with the other side and at least 30 seconds

- Single leg rise test >85% compared with the other side and >10 reps with each leg

- Single leg balance with eyes open=43 second hold and with eyes closed=9 second hold

- 1RM test single leg press =1 x Bodyweight

- 1RM squat to 90 degrees (can be hex bar squat, front squat, back squat etc.) =1 x Bodyweight

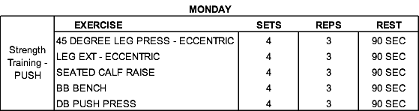

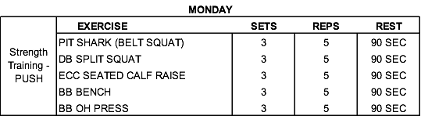

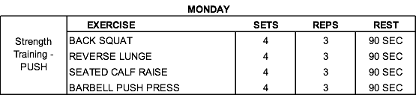

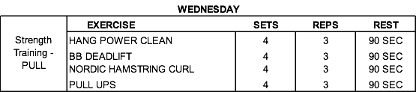

In this phase, I am training the non-surgical limb as the strength and conditioning coach. Since the PT was already training the surgical limb in the prior phase, I can accelerate the type of loading we are using during this phase. The leg extension is performed using a 2-up/1-down method which I classify as “eccentric” above, since we can have a larger load during the eccentric portion of the lift due to lowering with 1 limb. The volume of sets and reps is kept the same throughout the phases, but progressive overload is occurring on a weekly basis. Strength training is occurring on Mondays and Thursdays, while conditioning work is performed on Tuesdays and Fridays. Depending on the athlete, we may begin incorporating box drops or low-level box jumps at this point as a warmup to weight training in addition to beginning a dynamic warm–up.

The warm–up consists of basic mobility exercises and leg swings to encourage full range of motion at the hip, as well as sprint development drills like A-skips, skip variations, and shuffles. I may also begin bilateral pogo jumps in place with the goal of extending these out to 5 to 10m in the coming weeks. I typically end the session with some type of medicine ball throw to ensure we are still training some type of power/neural work during these general strength phases.

Conditioning may progress to include non-impact tempo/aerobic based interval parameters, as we are continuing to build the aerobic system. At the end of this phase, our PT is also performing the first phase of the Dynamic Movement Assessment looking at quality and equality of movements, quad strength, and the athlete’s ability to control the involved lower extremity.

Weeks 13-16: Maximal Strength

During this phase of training, more testing is performed by the strength and conditioning coach as the training is slowly progressing to include running, agility, and landings. Strength is still the major quality being trained—it is performed with higher absolute loads and with less reps than the previous cycle. The athlete will most likely be completing a return-to-run with the PT at this point, typically from Weeks 12 to 16, and will have been exposed to low level jumps and landings with myself and the PT. Once the athlete achieves the goals as outlined below, they progress into the next phase. The testing during this phase will most likely occur every 3 to 4 weeks, or as needed. The checkpoints for this timeline include:

- Star excursion test >95% compared with the other side

- Single leg rise test to 90-degree box with hands behind head >22 reps on both limbs

- Isometric mid-thigh pull on force plates to analyze peak vertical force and rate of force development

- Counter movement jump on force plates to analyze jump height and reactive strength index. This is done both double leg and single leg to look at force, as well as equality of loading.

- Broad jump for distance

- 1RM test single leg press =1.3 x Bodyweight

- 1RM squat to 90 degrees (can be hex bar squat, front squat, back squat etc.) =1.3 x Bodyweight

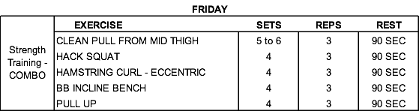

We progress to training 3x per week during this phase with 2 days of conditioning on Tuesdays and Thursdays. As noted in the tables, we are progressing to include more complex movements, such as the clean pull from mid-thigh and the hack squat, and we are including the 2-up/1-down method for the leg press, leg extension, and hamstring curl. The intensities are higher than the previous block, since we are now working in our 3’s block. The jump training is progressing at this point to include countermovement jumps, broad jumps, higher volumes of pogo jumps performed at distances of 10m, and short bounds during our warmups. All sprint development drills are occurring as we get closer to sprinting. At this point, using a sprint timing gate is encouraged to track growth. Since the athlete will be finishing the return to run program with the PT at this point, I will begin to introduce sprinting in short distances of 5-10m with submaximal intensity. Once the athlete is cleared by the PT, the sprint training will remain acceleration based at 10m; timing gates are used to record every rep to ensure max intensity and volume will continue to build during the next phase. Conditioning is progressed to include extensive tempo runs with short intervals/short distances depending on where the athlete is running. The conditioning occurs twice a week, with one day of tempo runs and one day of lactic power intervals on a bike.

Week 17-21:Basic Strength

Most of the training in this phase is performed by the strength and conditioning coach, especially as training becomes more specific and more complex. While strength is still the major quality being trained, we are shifting back to a 5’s block since newer exercises are being introduced. We will also transition into a power block during the final phase. Once the athlete achieves the goals as outlined below, they progress until the next phase. The testing during this phase will most likely occur every 3 to 4 weeks, or as needed. The checkpoints for this timeline include:

- Single leg vestibular balance test passing on both limbs

- Single leg forward hop test >95% compared with other side and equal to or greater than preoperative data

- Side hop test >95% compared with other side

- Triple hop for distance test >95% compared with other side

- Triple cross hop over test for distance >95% compared with other side

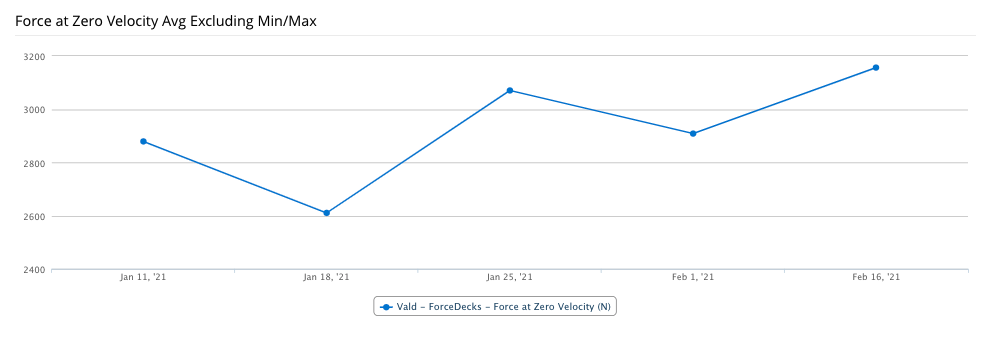

- Isometric mid-thigh pull on force plates. Peak force and RFD > previous test

- Countermovement jump on force plates. Jump height and reactive strength index > previous test

- Broad jump for distance > previous test

- 1RM test single leg press = 1.5 x Bodyweight

- 1RM squat to 90 degrees (can be hex bar squat, front squat, back squat etc.) = 1.5 x Bodyweight

- 10m sprint, assessing week to week

As noted in the tables, we continue to train 3x per week at a higher intensity Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and 2 days of lower intensity conditioning on Tuesdays and Thursdays. We progress to include more compound and complex movements like the front squat, deadlift, hang power clean, and split squats. At this point in the training, I begin to utilize a “sprint first” approach and begin to structure our weight room work around sprinting. Our sessions begin with a warmup, followed by sprint development drills, acceleration, multi-jumps, and end with strength training. Our main goals during these sessions are to train repeated sprint ability, introduce change of direction work, and progress to true plyometrics to train the elastic response. The sprint work is considered acceleration, as we are training in the range of 10 to 40m and some of these sessions may occur with a sled to teach the athlete to put force into the ground. The change of direction work includes re-education on how to properly cut. The multi-jumps become more complex as we begin to include exercises like hurdle jumps and extended bounds. The conditioning during this phase builds upon the extensive volume of tempo runs that we performed during the last phase and is meant to serve as low intensity days of training on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Communication is again important during these advanced progressions as the PT will begin to focus more on controlled lateral movements and stability of the involved leg. This prepares the athlete for higher level change of pace/direction and reactive movements that will be performed with the strength coach in the next phase. PT activities also include learning controlled deceleration from sprinting at the end of this phase.

Weeks 22-25: Power

During this phase of training, the athlete is nearly back to 100% of activity with the strength coach and will begin practice activities at 6 months post-op including warm-up, technical drills, and skill activities that do not include open environment play. At this point, PT will focus on tolerance and control of more reactionary movements, as well as progression of sport specific change of direction and pace activities on the soccer field. The PT will incorporate sport specific drills. Power is the main quality being trained, as we shift into a 3’s block of training with the intent to move loads as fast as possible. The testing that occurs during this phase is to ensure the athlete is ready for the reactive demands of their sport. The checkpoints that occur during this timeline include:

- Isometric mid-thigh pull on force plates (peak force and RFD > previous test)

- Countermovement jump on force plates (jump height and reactive strength index > previous test)

- Broad jump for distance > previous test

- 1RM test single leg press = 1.8 x bodyweight

- 1RM squat to 90 degrees (can be hex bar squat, front squat, back squat etc.) = 1.8 x bodyweight

- Sport–specific agility test

- Sport–specific conditioning test

We continue to train 3x per week at a higher intensity, and 2 days of lower intensity conditioning on Tuesdays and Thursdays. We build upon the same structure of training from the previous phase, but we may use one day for top speed and the other 2 days for high neural work, serving as reactive agility days. The multi-jumps are progressed to include an introduction to depth jumps and an emphasis on single leg reactive strength. The tempo runs may be progressed in volume, but it depends on how much activity the athlete is performing during practice. Depending on the demands of the athlete’s sport, we may run a Y shaped reactive agility test and a pro agility test to compare with pre-injury scores. The sport specific conditioning test provides the athlete with the confidence and comfort knowing they are adequately prepared to return to their sport. As strength and sport ability grow, along with athlete confidence, the athlete is progressed back to full practices around 7-8 months post-op, and back to full open environment contact practices and games participation at 9 months post-op.

This protocol was developed with the assistance of DePaul’s Director of Sports Medicine, Sue Walsh, and our physical therapist, Ted Kurlinkus. Much of this information was based off of material found in the Melbourne ACL Rehabilitation Guide 2.0 by Randall Cooper and Mick Hughes, and by material created by Boo Schexnayder.

Ryan Nosak is the Assistant Director of Sports Performance at DePaul University. Nosak primarily works with the cross country, golf, women’s soccer, and track and field programs while also assisting with the men’s basketball team. Prior to DePaul, he primarily handled the sports performance duties for women’s basketball and men’s tennis at Charlotte as Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach. He was an Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach at Robert Morris University in 2014-15 and worked at Vanderbilt (2014), Tennessee State (2013-14) and Penn State (2011-13). He completed his undergraduate degree from Penn State in 2013 and holds a master’s degree from Western Carolina University. He is Strength and Conditioning Coach Certified (SCCC), a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), a Certified Speed and Agility Coach (CSAC), RPR Level 1 Certified, and USTFCCCA Strength and Conditioning Certified.

REFERENCES

Doherty, Madigan, Warrington, & Ellis. (2019). Sleep and Nutrition Interactions: Implications for Athletes. Nutrients, 11(4), 822. doi:10.3390/nu11040822

Guo, J., Qu, W., Chen, S., Chen, X., Lv, K., Huang, Z., & Wu, Y. (2014). Keeping the right time in space: Importance of circadian clock and sleep for physiology and performance of astronauts. Military Medical Research, 1(1), 23. doi:10.1186/2054-9369-1-23

Hendy, A. M., & Lamon, S. (2017). The Cross-Education Phenomenon: Brain and Beyond. Frontiers in Physiology , 8. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00297

Yeh, D. D., Peev, M. P., Quraishi, S. A., Osler, P., Chang, Y., Rando, E. G., . . . Velmahos, G. C. (2016). Clinical Outcomes of Inadequate Calorie Delivery and Protein Deficit in Surgical Intensive Care Patients. American Journal of Critical Care, 25(4), 318-326. doi:10.4037/ajcc2016584

Recent Comments