The in-season period is often the most challenging time for a sports performance coach in the college setting due to limited opportunities for athlete recovery. Frequent competitions, travel, midterms, and other factors make this a very stressful time for both athletes and coaches. Many say the number one role of a coach is managing stress. We know athletes are humans first and have a multitude of factors contributing to their total amount of stress. With this knowledge, it is important to be able to monitor how athletes are handling training and competitions so we can help them be at their best when it matters most.

In terms of “recovery,” any method which can influence positive change can be considered a recovery tool. Strength and conditioning coaches may read “‘positive change”’ as adaptation. Positive changes can and do occur around the clock. As Fergus Connelly so beautifully states in his book 59 Lessons, “Everyone trains for 2 hours. The other 22 are what matter.” This means, as coaches, we can potentially influence an athlete’s entire day. Now, this shouldn’t necessarily be the goal of a coach when it comes to recovery. However, it does show how a coach who pairs knowledge with influence can have a profound impact on their athletes’ wellbeing.

ATHLETE WELLNESS QUESTIONNAIRES

Implementation and prescription of various modalities for recovery had a general blueprint but often went in many directions. As a staff, the sports performance team structured a flow chart from less aggressive to more aggressive modalities. This was done to encourage small doses of consistent modalities early, rather than reacting with the most potent modality with no previous attempt to solve any issues.

As an example, using a foam rolling/stretching routine before going into the cold tubs was an attempt to solve the issue without resorting to the last option. With certain athletes that play a high percentage of their competitions, using their data along with conversations on an individual level was used to prescribe recovery. With one athlete in particular, she reported “heavy legs” and was playing almost every minute of every game. We decided to use cold tubbing on days further from game days, and contrast baths closer to gameday. Based on her feedback, this appeared to maximize her ability to practice, lift, and train hard while also preparing her body for competitions on weekends.

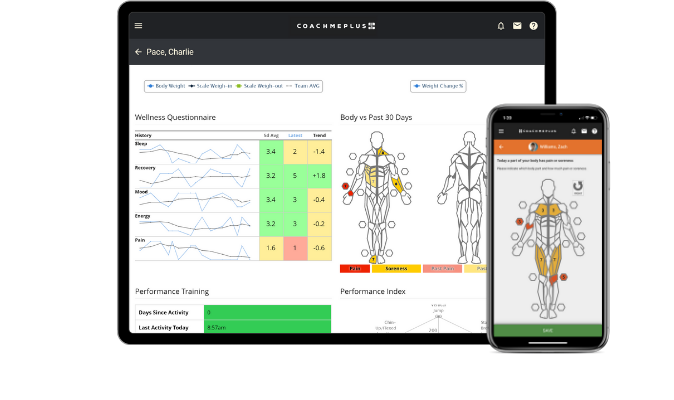

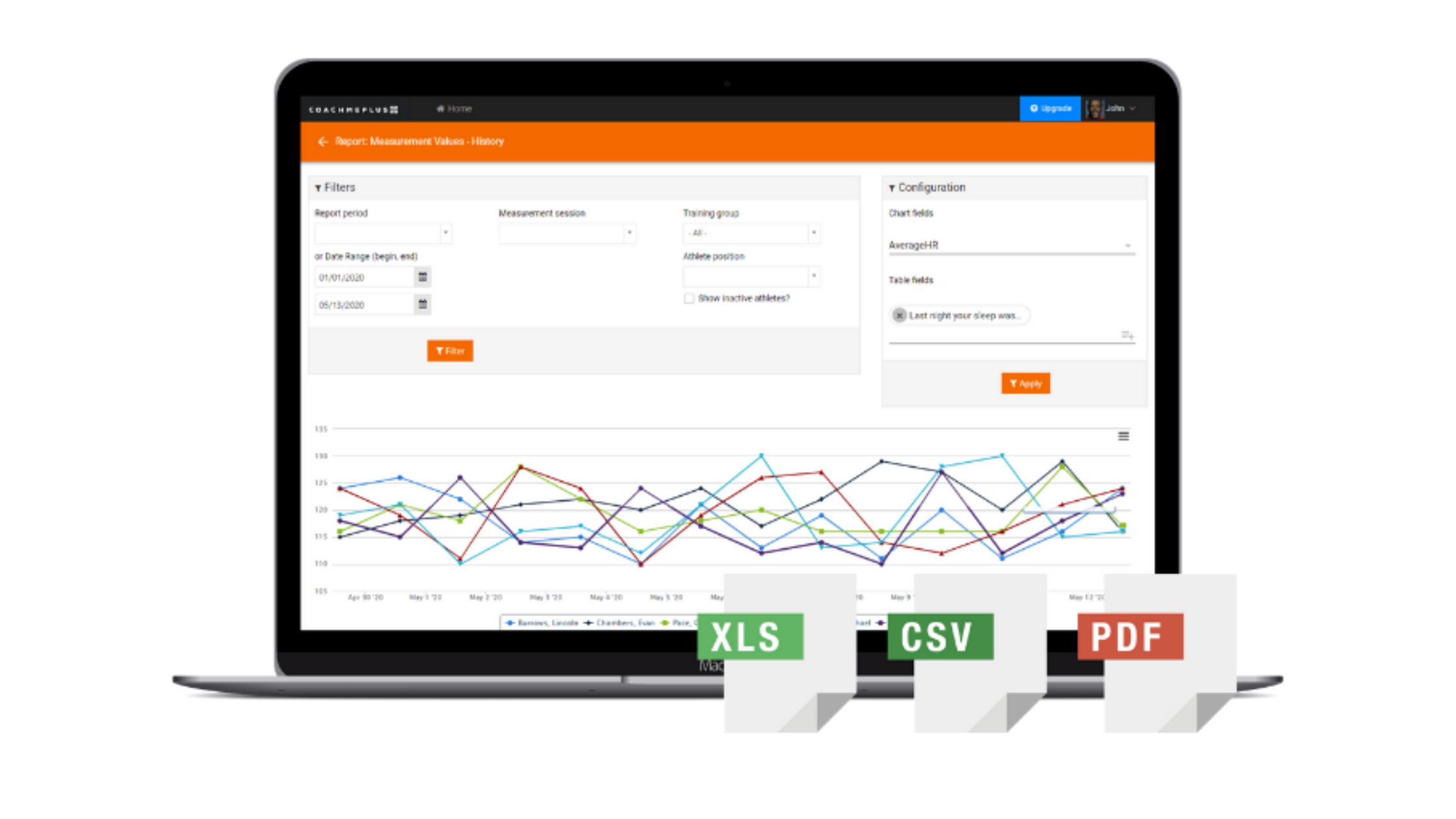

COACHMEPLUS – ATHLETE RECOVERY MONITORING

Another athlete reported nothing noteworthy except the same heaviness in her legs. Her performance data and wellness data both looked normal, but we had a conversation about what she might be able to do. During the conversation, she reported sleeping about 8 hours most nights, but the sleep wasn’t as restful as before. Her high-minutes also put a demand on her to fuel properly with nutrition, which after talking seemed to be lacking especially with carbohydrate intake. After implementing a pre-sleep routine to help sleep deeper and improving carbohydrate intake, she reported feeling much better. The performance data (jumps and sprint speed) were collected to use as an educational tool as well as last buffer to drive adjustments. The coaching staff places a high emphasis on speed, so if we saw numbers dropping too much, it is another check to adjust their training.

These examples are just a few of the many cases that have been managed successfully. Looking back, the key takeaways in running a successful in-season program are to over-communicate between staff and athletes, take a holistic approach to monitoring and implementation, and work year-round to build trust and influence within your team. In the future, better education from the coach to athletes can help drive more ownership of the process of training and recovery. The more athletes feel they are in control and are empowered to be a part of their own process, the better the results will be. Recovery is a never-ending process, and one aspect will affect another. Poor sleep affects nutritional choices which may affect soreness and ultimately may impact how much/which recovery modality you need. The biggest driver to proper recovery lies in executing the somewhat boring but productive aspects daily, not simply jumping in a tub once in a while. Once athletes understand all the little choices they make add up, and how the sum is greater than its parts, incredible peaks can be reached.

Recent Comments