The Severity of Traumatic Brain Injury

Nearly every sport has direct risk of TBI from games or competition, or from training. Contact sports and team sports have higher rates of risk, while endurance and Olympic sports tend to have fewer incidents overall. Generally, the greater the participation in contact sports, especially collision and combat sports, the more likely an injury to the brain will occur. All levels of sport are at risk, as youth populations as well as elites face the same obstacles of managing and reducing TBI. Statistically, in the United States alone, over a million estimated incidents occur per year based on current research, and that number will likely change and possibly grow as diagnosis and awareness increase. Each sport, participation level, and league has their own data on rates of TBI, but as the ability to diagnose all trauma to the brain grows, we will likely see a wider range of injury types and an increase in probable injury.

Long-term data is less conclusive, but the pattern of severe injury and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is of concern due to the repeated reinjury rate with concussions from collision and combat sports, and from a lack of proper head injury management. While the problem appears to be treatable, no comprehensive cure exists as of today for CTE. There needs to be ongoing research and new approaches for treating TBI and CTE, as well as medical therapies for similar brain conditions.

Screening of the Athlete

The goal of screening is multipurpose, meaning there are several benefits to the annual athlete evaluation process. Professionals screen athletes not just to see who is at risk or who may have lingering effects from a previous TBI, but also because the process creates a necessary baseline. Screening also educates the athletes. Without screening, most of the reactive responses would likely be impaired and less effective.

Clearance from former injuries can sometimes be mistakenly done too early; thus, repeated screening has the potential to catch a lingering problem before competition resumes the next season. Ideally, the concussed athlete returns to sport after proper medical clearance, but due to the clinical symptoms being difficult to interpret with some athletes, it’s likely that some athletes will return too early. Therefore, additional evaluation from conventional screening enables the medical staff to flag athletes who are still suffering from earlier injuries, and proper care can be administered.

Diagnosis and Care of the Brain and Spine

The proper diagnosis of a TBI requires medical expertise and should incorporate as many professionals as necessary to support the return-to-play process. A trained medical doctor skilled with diagnosing sports concussion must be involved with proper early care. Currently, sideline support is the standard in elite sport, but at lower levels it’s difficult to have expert medical professionals readily available. In addition to the neurological component of the injury, post injury evaluation of the spine and extremities is also a responsible approach.

Outside clinical evaluation by the medical staff, imaging of the brain is subject to debate. Since it’s likely that conservative care will have more false positives, imaging may not be necessary if the symptoms are mild. There is currently no gold standard for an individual test to diagnose a sports concussion, but the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer tomography (CT) can assist in the diagnosis of TBI. MRI and CT scans are part of the equation, and clinical evaluation is the driver of most return-to-play approaches.

Additional testing of the function of the central nervous system (CNS) is necessary, as any injury should have a process to rehabilitate the loss of functional abilities. A market for both education and instrumentation exists, focusing on vestibular testing, coordination assessment, reaction and vision evaluation, and other measurements of the CNS. Additional subjective and qualitative evaluations from medical staff are extremely valuable, as the available testing equipment requires athlete feedback.

Prevention and Response Opportunities

Most of the risks of concussion are due to the composition of factors of the sport itself, meaning how the game is played and prepared for. Rugby, American football, and even soccer are problematic because the rules and strategies expose the athlete to risk. Preparing the athlete for success on the field will come at a cost, and usually that is the health and well-being of the athlete in the long run. Therefore, policies must be instituted where a boundary that cannot be crossed is in place, and that boundary is the long-term brain health of the participants. The research on CTE is clear: Athletes with permanent brain damage risk severe long-term health problems and suicide. The ethical prevention and reduction of the severity of injuries require policies that are based on the best-known and conservative care available.

Outside of rule changes and practice adjustments, the preparation of the neck and biochemistry of the body are the two leading areas that contribute the most to prevention. If a TBI occurs, both could reduce the severity of the injury, thus showing that preventive measures are invaluable. General training, specific neck training, and careful nutrient balance have all shown to contribute to a reduction in the rates of injury and the potential magnitude of the injury. Efforts to predict risk from neck circumference and actual strength indices are promising, but they are all limited at this time. The current interest in creatine and omega-3 supplementation is encouraging, but no consensus opinion exists on the extent of the effectiveness of those preventive and supportive measures with TBI in sport.

Monitoring and Testing the At-Risk Athlete

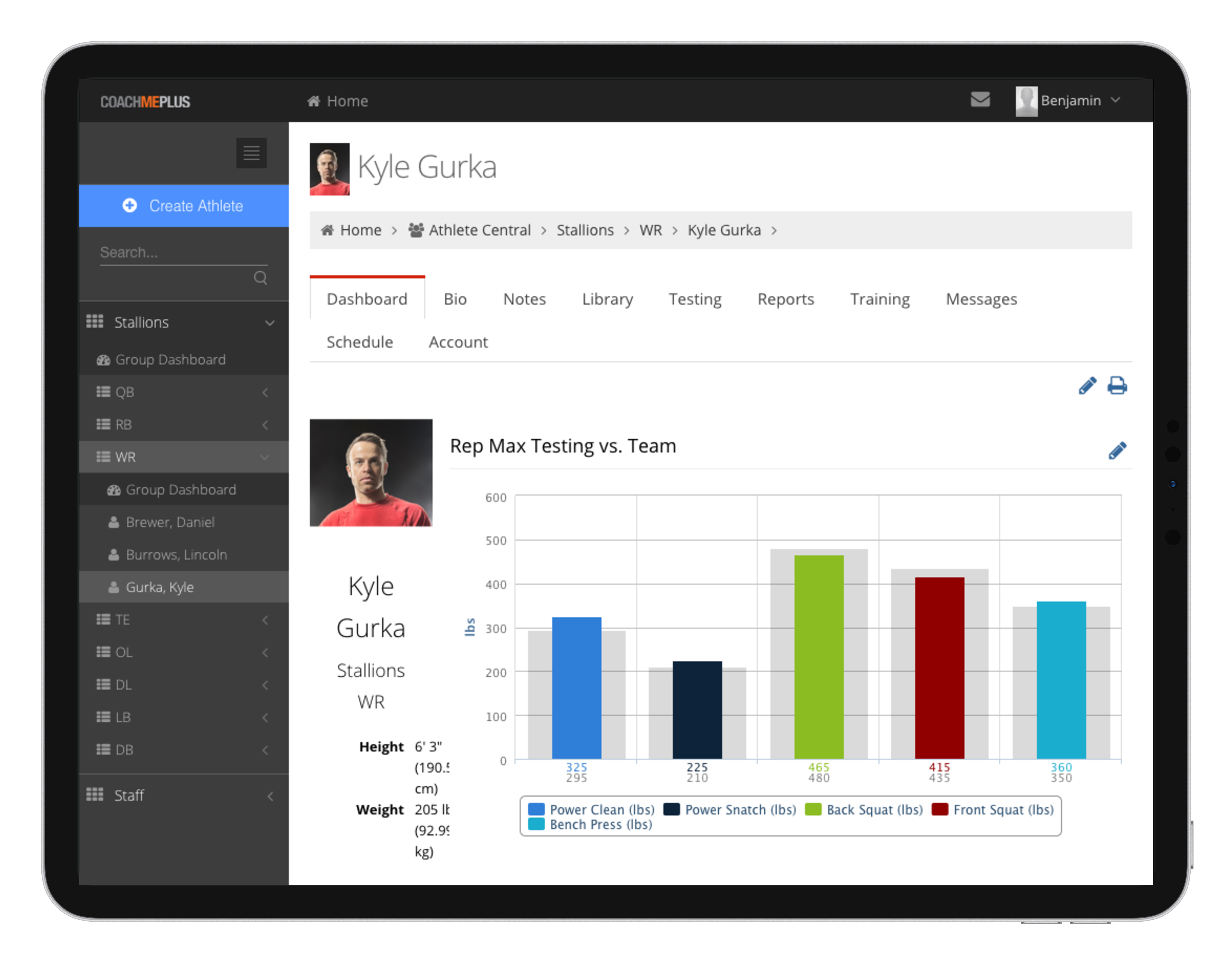

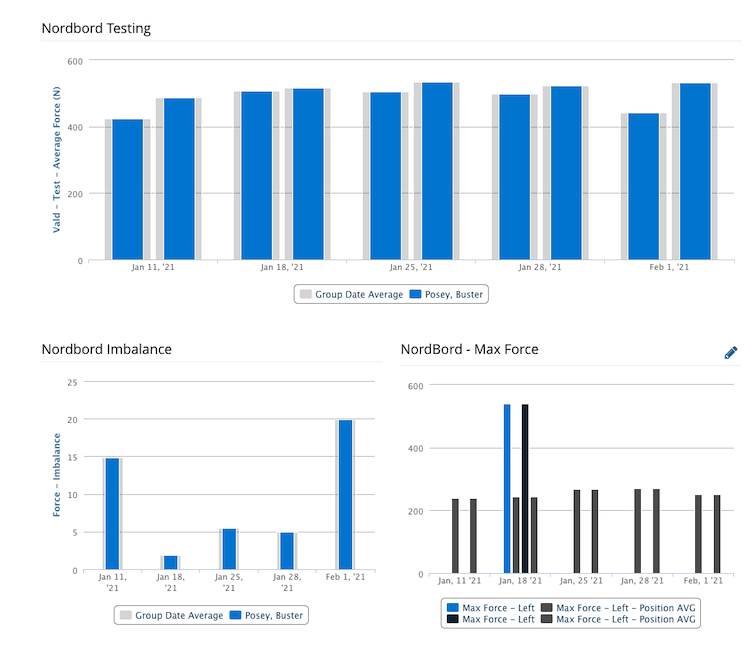

As mentioned earlier, clinical evaluation is essential to properly manage and organize an injury, but further testing and monitoring are essential as well. After injury, an athlete needs to be monitored not just daily, but also before and after treatment and training. An injured athlete can improve their outcomes with better decision-making in rehabilitation, and the right choices come from experienced staff having access to the best information. Proper monitoring employs the most efficient and accurate data that assists staff, and monitoring the subjective clinical responses from a concussion and testing the abilities of the athlete post injury are vital.

Monitoring changes and physiological responses with training and rehabilitation improves the return-to-play process, as it fosters communication and allows all involved to have access to essential information. Milestones that are measurable and demonstrate definitive progress should be included in the monitoring process to add clarity to the return-to-play program. Monitoring should be multidisciplinary and include all support staff in the decision-making to safeguard against additional injury and poor performance upon return.

Testing the athlete is a continuum of basic health functions all the way to elite performance. While it’s important to have quantitative data, a sport coach should be included in the return-to-play process. Emotionally, an athlete who is ready must be confident or they risk additional injury or poor performance if they are not sure if they are actually ready, and an athlete who does not appear fully rehabbed should be held out by the coach if it’s warranted. Finally, the athletes themselves must be honest in the process since they are the ones who are directly exposed to risk, and we should hear their voice in the matter if they don’t feel they are indeed ready. Athlete questionnaires are a simple item to implement across even large teams giving coaches the subjective data to make a return to play decision.

Protecting the Head and Spine in the Future

The primary issue with athlete safety at the professional level is an ethical dilemma of how the game is played and how fans expect athletes to play when winning matters. Rule changes have been made and new policies have been created to protect the athlete, but unfortunately, simple screening, proper diagnosis, and return-to-competition practices still lag far behind best practices. Support staff members have the opportunity to educate the athlete and prepare them properly with both training and nutritional approaches. Down the road, more research and better methodologies should help improve outcomes of TBI, but it’s up to the coaches, administrators, and athletes themselves to make the right decisions for proper treatment of those that do get injured.

CoachMePlus is a comprehensive solution for any training environment, ranging from scholastic level to pros, and including both military and private facilities.

Recent Comments